Beyond Tokens: The Context-Window Perspective on LLMs, Memory, and Mind

Exploring the bridge between next-word prediction, agent frameworks, and the limits of current LLMs consciousness

3rd July 2025

This article expands on ideas I first presented during a keynote at an AI Hackathon organized by Fotocasa. I am grateful to the organizers for inviting me.

Large Language Models don’t work the way most people think they do. They are massive neural networks with billions of parameters (neuronal connections), but when they’re generating responses (making an inference), they remain static: their internal state doesn’t change.

The goal of this article is to demystify some of the inner workings of Large Language Models and explain how agentic behavior can be achieved. All from the perspective of the model’s input, which makes it very intuitive.

But what is a Large Language Model?

You might not realize it, but your phone has had a language model for over 10 years. Not a large one, but it’s there. It’s used to predict the next word you’ll type.

Language models do exactly that: from a limited vocabulary (usually tens of thousands of the most common words) they choose the most likely next word given the previous context. They accomplish this based on the vast amounts of data they were trained on.

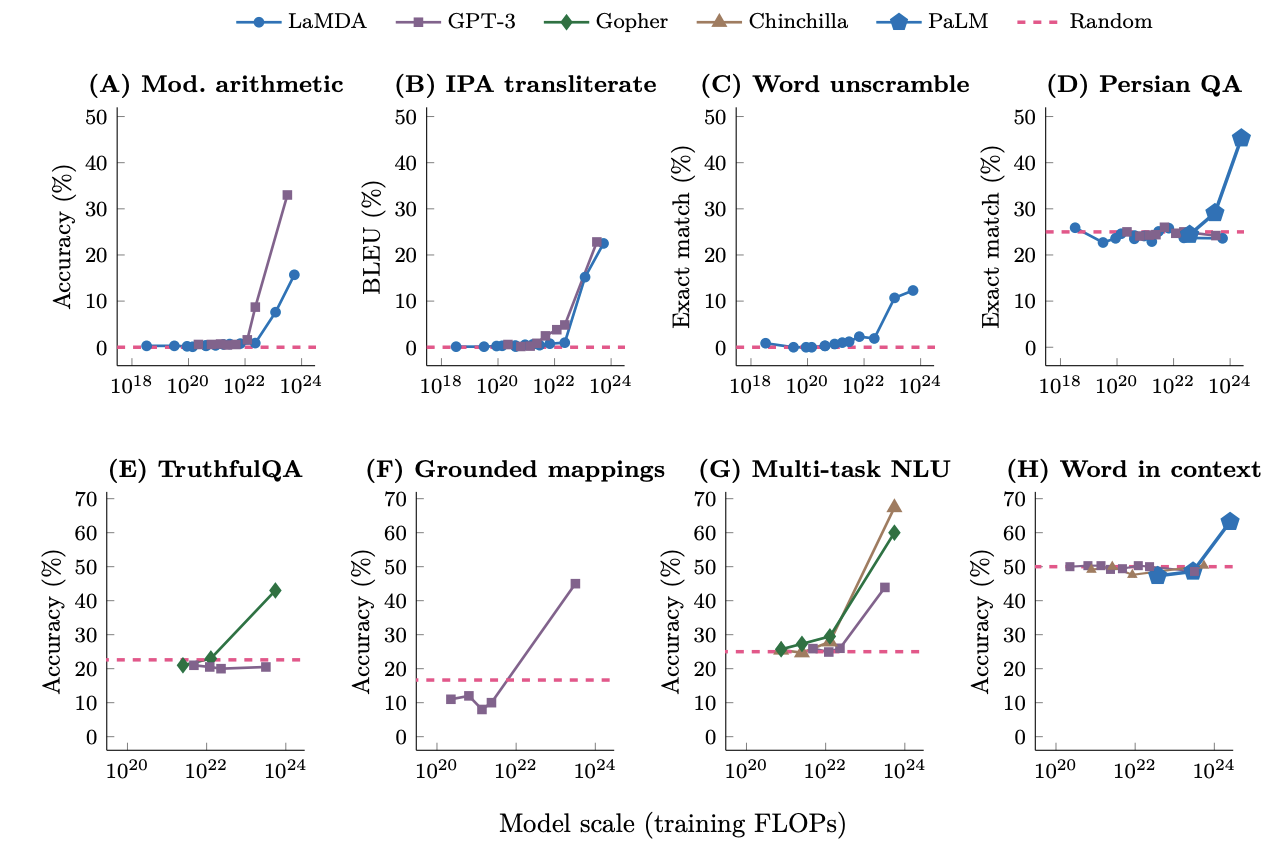

Something fascinating happens when you scale up these models. By increasing both the number of parameters and the training data, the model suddenly becomes dramatically more powerful. Think of a parameter as a neural connection between two neurons, current largest models reach into the trillions of parameters (e.g., Llama 4 Behemoth).

This performance change occurs almost like a phase transition: suddenly, when the model reaches a certain size and training duration (with sufficient data), it acquires entirely new abilities. This phenomenon was thoroughly documented in the paper Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models, and the scaling laws are also summarized in Opening the LLM pipeline.

In reality, LLMs don’t predict the next word, they predict the next token, which represents an optimal compromise between predicting individual characters and entire words. On average, a token corresponds to about 0.8 words. For simplicity, I’ll use “words” and “tokens” interchangeably throughout this article.

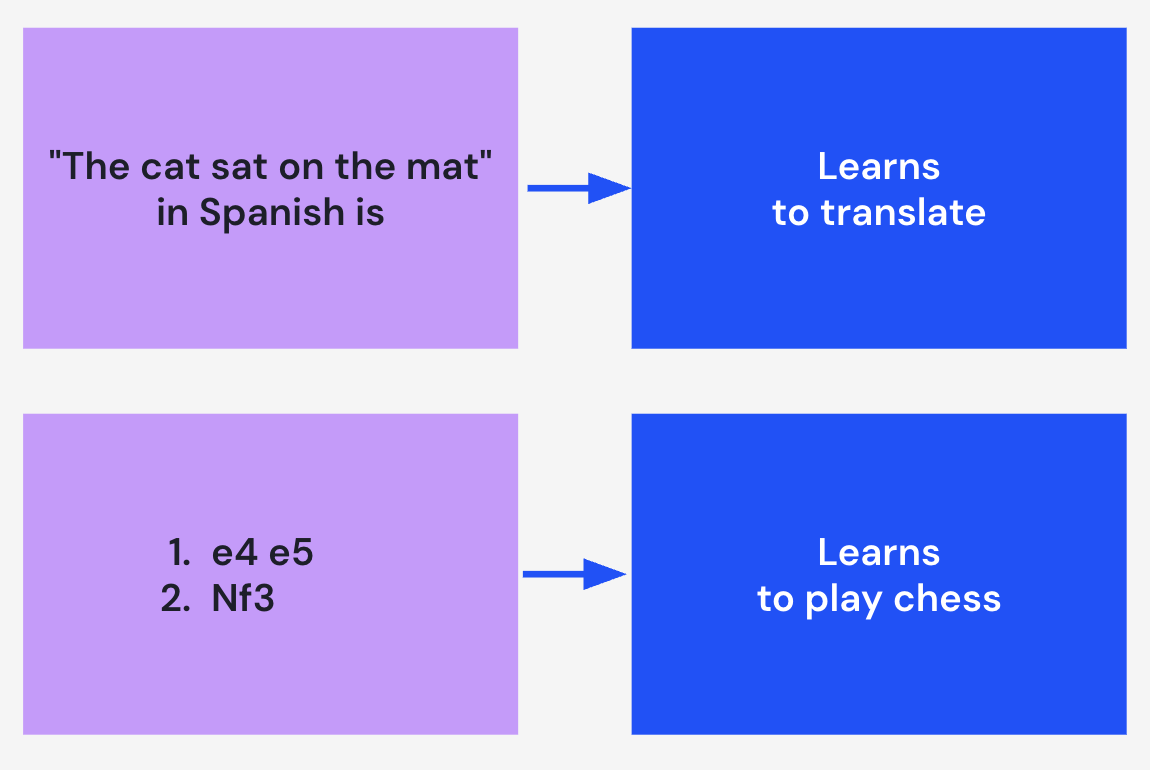

The task of predicting the next word is surprisingly profound. Consider this prompt:

"The cat sat on the mat" in Spanish is

To predict the next set of tokens, the model needs to understand how to translate from English to Spanish:

"El gato se sentó en la alfombra"

Or consider this more complex example:

You are a Grandmaster chess player. Predict the next move:

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Nf6 5. Nxf6+ exf6 6.

Here, the model needs to understand chess strategy to suggest a good move.

Therefore, predicting the next word requires learning to translate, play chess, write poetry, code, and much more. Essentially learning about the world itself. As Ilya Sutskever said, “text is just a projection of the world.”

From LLM to Chatbot

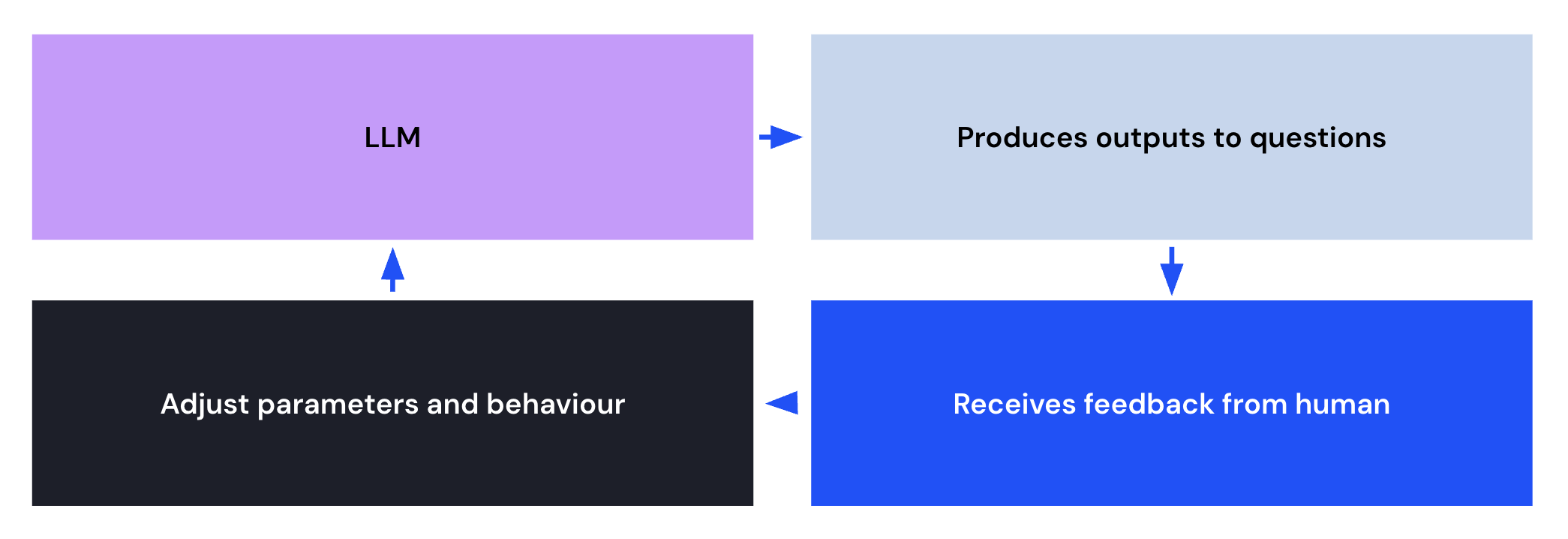

While LLMs are powerful on their own, creating a chatbot like ChatGPT requires additional steps. Chatbots need to maintain coherent conversations, which demands more than just next-token prediction. This is where reinforcement learning comes into play. In simplified terms, the process to go from an LLM to a chatbot with certain characteristics looks like this:

Starting with a raw LLM, we ask it to produce several answers to the same question. These answers are then rated by humans based on various criteria (usefulness, truthfulness, helpfulness, etc.). The ranked responses are used—through a process that may involve another model to retrain the LLM by readjusting its parameters. This process repeats iteratively until the model reaches a satisfactory state.

The Context Window

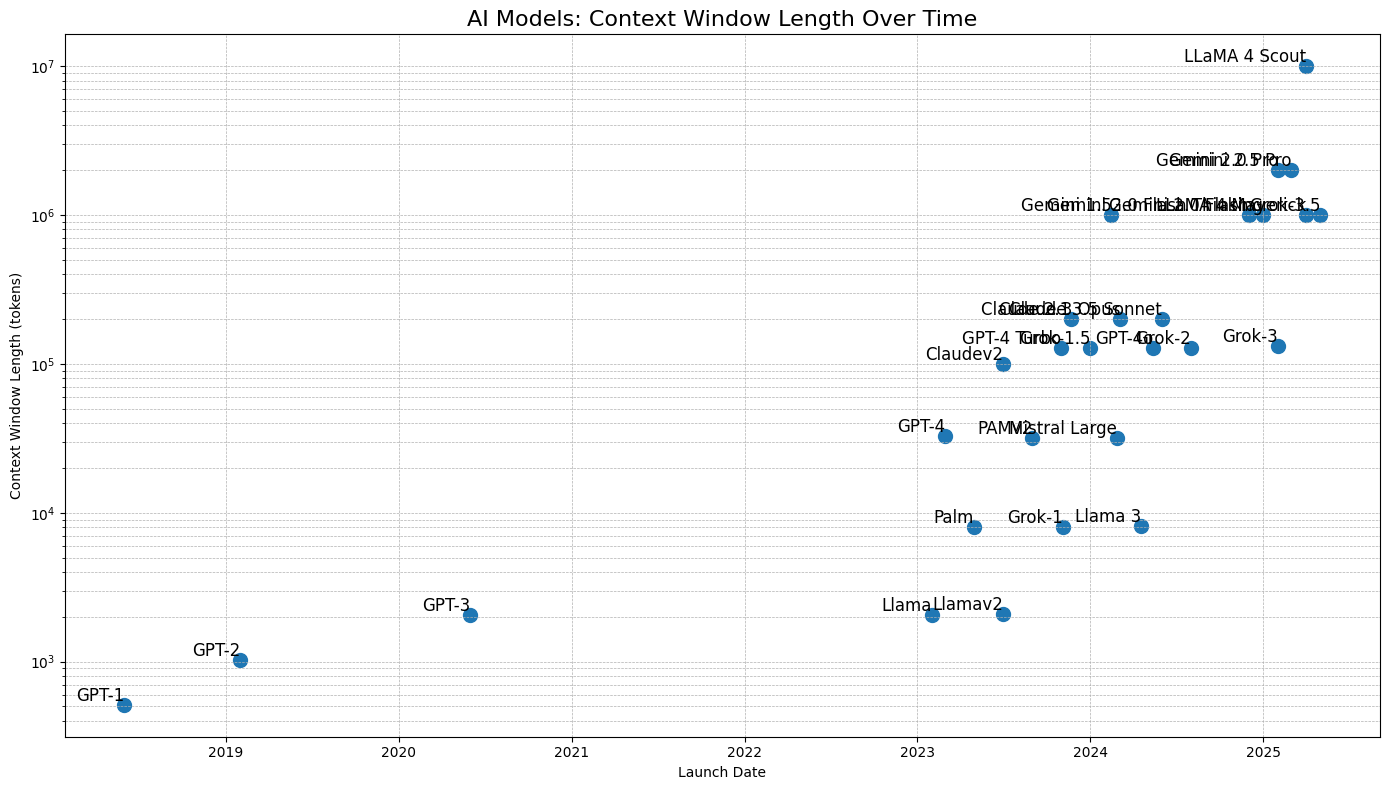

The context window represents the input to the LLM, essentially the set of tokens the model uses to predict the next one. Each LLM has a different context window size, as most architectures require quadratic scaling with size (though there are exceptions). The LLM with the largest context window (Llama 4 Scout) can process 10 million tokens, which is roughly equivalent to the first 5 volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Are models with larger context windows necessarily better? The trend over the past few years has been exponential growth, until recently. With the introduction of reasoning models in the last year, this trend has plateaued. This shift occurs partly because reasoning models iterate over input data in an “agentic mode”, working with summaries and strategically manipulating the context window to reach final answers. More on memory and agents later.

Examples of Calls to LLMs

When we write somethingto an LLM, we’re actually sending a request to the trained neural network. This process of reading from the context window and generating predictions is called inference.

What we write to the model is called a prompt, which gives rise to the term prompt engineering: the art of crafting prompts that produce desired outputs. As some have noted, a more accurate term would be context engineering.

How does this work in practice? Let’s examine some examples. The call to the LLM is typically formatted as JSON, though what actually enters the context window is just a string. Here’s a simplified example of what this JSON looks like:

{

"messages": [

{ "role": "system", "content": "You are a playful assistant." },

{ "role": "user", "content": "Hi!" }

]

}

The first message of the request above is the system message, which instructs the model on how to behave and can contain custom instructions. We’ll see more applications of this later.

The second message is the user message: what the user has written. Together, these elements form the prompt. The model then generates a response. Technically, the model doesn’t produce a complete response at once, but generates one token at a time in a loop, reading the entire context window plus the newly generated token each time, until it produces a token that signals the end of the response. While this isn’t shown in the JSON format, it’s important to understand this mechanism.

The response of the model can look like this:

{

"messages": [{ "role": "assistant", "content": "Hey there!" }]

}

When the user asks another question, the entire conversation history is sent to the model again:

{

"messages": [

{ "role": "system", "content": "You are a playful assistant." },

{ "role": "user", "content": "Hi!" },

{ "role": "assistant", "content": "Hey there!" },

{ "role": "user", "content": "Can you tell me a joke?" }

]

}

The model generates a response, and this process continues.

As mentioned earlier, what actually enters the context window differs from the JSON format and looks like this in its raw form:

<|im_start|>system

"You are a playful assistant.

<|im_end|>

<|im_start|>user

Hi!

<|im_end|>

<|im_start|>assistant

Hey there!

<|im_end|>

<|im_start|>user

Can you tell me a joke?

<|im_end|>

where the <|im_start|> and <|im_end|> are actually tokens that mark the start and end of the message.

Past memories

Many current LLM providers, such as OpenAI, have memories. So, if the neural network is static, how is this done?

Again, through the context window. The model will store selected parts of the conversation (one can imagine an LLM runnning in the background that does that), and then adds them to the context window.

The call to the model can look like this:

{

"messages": [

{ "role": "system", "content": "You are a playful assistant." },

{ "role": "memory", "content": "User name is Manuel." },

{ "role": "memory", "content": "User is from Spain." },

{ "role": "user", "content": "Hi!" },

{ "role": "assistant", "content": "Hey there!" },

{ "role": "user", "content": "Can you tell me a joke?" }

]

}

where memories are incorporated as a special message type.

Consciousness?

When using very powerful models that can engage in seemingly fluent conversations, it’s natural to believe the it possesses some sort of consciousness, as the responses are almost human-like. By looking at the mechanics just explained, we can see that if any form of consciousness exists, it’s fundamentally different from human consciousness.

First, the LLM’s neural network remains static: it doesn’t change. Therefore, there’s no evolution, no new memories are stored within it, and it doesn’t remember previous conversations or experiences. The model only responds to what’s in the current context window. It’s purely a function of its input: a function in the strict mathematical sense.

Second, the neural network only activates during next-token prediction. If any form of consciousness exists within this network, it only lasts for the duration of this prediction process, with the context window’s content being a crucial component.

I believe the next generation of AI should address this limitation: creating systems that evolve over time (with dynamic neural networks) and can independently store memories. This might involve incorporating retraining mechanisms, or even systems where new neurons are added and others removed.

Agents

Agents do much more than simply respond to prompts. They can search the internet, call internal functions or external APIs, access past memories, etc. By examining the context window, we can understand how they work.

Let’s consider a simple agent that can call a calculator function. Here’s how the conversation unfolds in the context window:

First, the system message instructs the agent about its capabilities and how to use the calculator function. This is followed by the user’s question, which will trigger a multi-step process:

{

"messages": [

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are an agent that can call a calculator function.

The function `call_calculator` expects a JSON object with a single

field `expression` containing a valid math expression and returns

a JSON object with a field `result`."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is 12 × 7?"

}

]

}

The agent responds by indicating it needs to use the calculator:

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "I need to multiply two numbers. Action: call_calculator",

"function_call": {

"name": "call_calculator",

"arguments": {

"expression": "12 * 7"

}

}

}

An external system parses this response, calls the calculator function, and adds the result back to the context:

{

"role": "function",

"name": "call_calculator",

"content": "{\"result\": 84}"

}

Finally, the LLM sees this result and provides the final answer:

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "Observation: The calculator says 84. Final Answer: 12 × 7 = 84."

}

The complete conversation in the context window looks like this:

{

"messages": [

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are an agent that can call a calculator function.

The function `call_calculator` expects a JSON object with a single

field `expression` containing a valid math expression and returns

a JSON object with a field `result`."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is 12 × 7?"

},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "I need to multiply two numbers. Action: call_calculator",

"function_call": {

"name": "call_calculator",

"arguments": {

"expression": "12 * 7"

}

}

},

{

"role": "function",

"name": "call_calculator",

"content": "{\"result\": 84}"

},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "Observation: The calculator says 84. Final Answer: 12 × 7 = 84."

}

]

}

More complex agentic behaviors work similarly: function calls (internet searches, API calls, memory access) are all added to the context window, enabling the LLM to produce appropriate responses.

Building agents involves more than just a context window and an LLM, you typically need a model-agnostic orchestrator (like LangChain) that manages state & memory (buffers, summaries, vector stores), tool routing (function calls, search, code execution, APIs), multi-step planning with sub-agent spawning, and observability (tracing, cost tracking, evaluation pipelines); though this may feel overly complex for smaller projects.

The Journey Continues

In this post, we’ve explored several key concepts: the context window, tokens, prompt engineering, LLMs as mathematical functions, agentic behavior, and memory systems.

This represents just a small portion of the broader LLM ecosystem. Many more concepts await exploration: embedding databases, RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation), reasoning models, MCPs (Model Context Protocol), and beyond. I encourage you to continue learning about these technologies and, most importantly, to start experimenting with them in your own projects.