Selected ideas from NeurIPS 2024

NeurIPS 2024, the largest AI research conference, provides a glimpse into the next frontiers. Here are some of the most exciting ideas presented.

1st February 2025

NeurIPS is widely considered the major AI research conference. With over 16,000 participants, 56 workshops, countless parallel tracks, and a staggering 3,650 posters, this event is more than just a conference: it offers a privileged vantage point into the state of the art in the field and their current challenges. The 2024 edition was hosted in Vancouver, during 6 packed days.

While it’s impossible to capture its vast scope in a single post, here’s a glimpse of the most exciting ideas that stood out to me.

Agents, the next frontier

Advancing intelligent systems requires shifting focus from standalone models (e.g., LLMs) to more complex, agent-based architectures capable of autonomous reasoning and decision-making. See for example the latest releases of frontier labs, such as o1 from OpenAI, DeepSeek, etc, where agentic methods like Chain of Thought are becoming more common.

There were many interesting presentations on the topic, including showcases of agentic libraries, such asAutogen, presented by Microsoft, or Llama Stack, by the folks of Meta.

Conquering human user interfaces

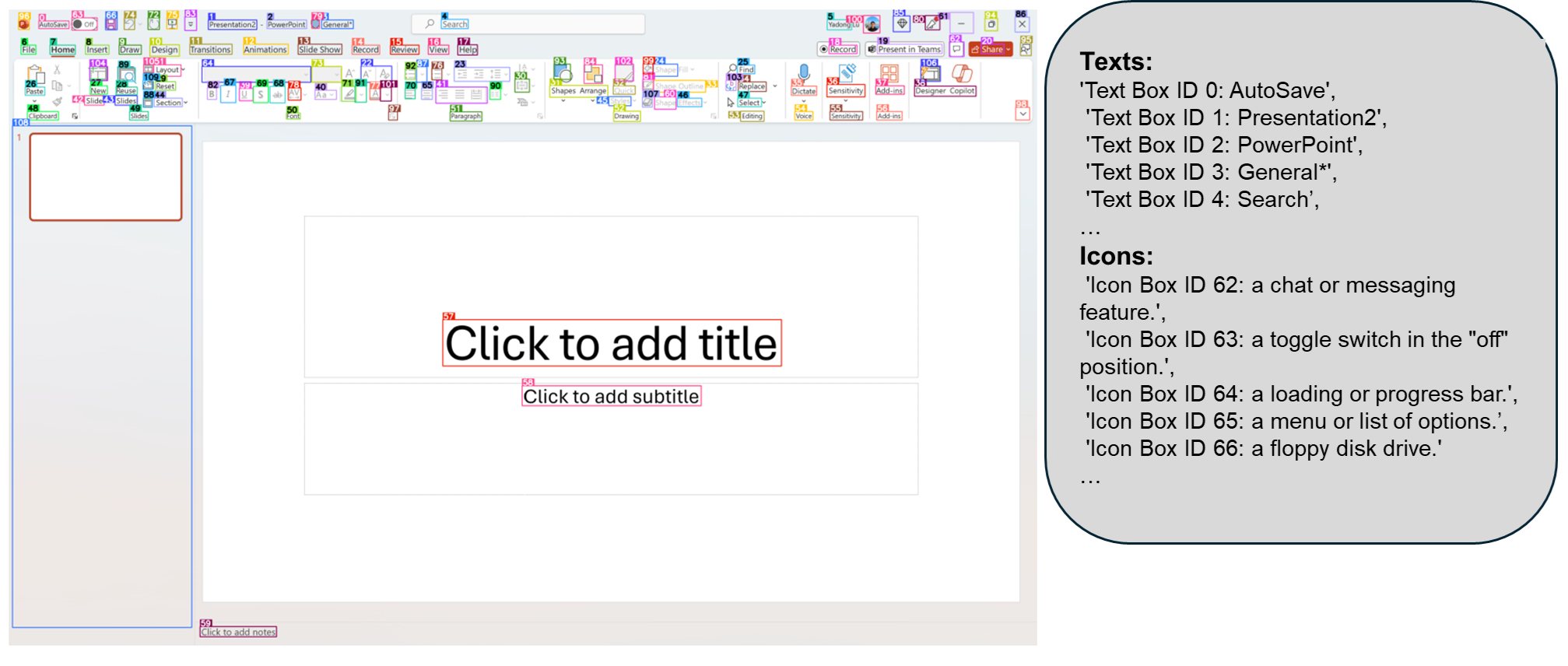

OmniParser, also from Microsoft, is a promising framework that provides more information to a multimodal LLM about the content of a screen or browser, drastically facilitating the interaction of the model with user interfaces. Solving this problem is key to have true agents in our phones or computers.

A key limitation, as I have observed in my own tests, is that feeding raw screenshots or HTML to a multimodal LLM (e.g., GPT4V) and granting it control over the mouse and keyboard results in poor performance on UI-driven tasks like booking flights or hotels. This is reflected in the low accuracy on GUI task oriented benchmarks, such as the ScreenSpot benchmark, where GPT4V arrives to 16% accuracy.

However, if the model is supplemented with the input coming from Omniparser, accuracy jumps to 73% on the same dataset. This has been surpassed by other models, which means that in less than one year, we will likely see AI operating seamlessly with the UI of our phones or computers as humans do.

Other useful resources about Agents

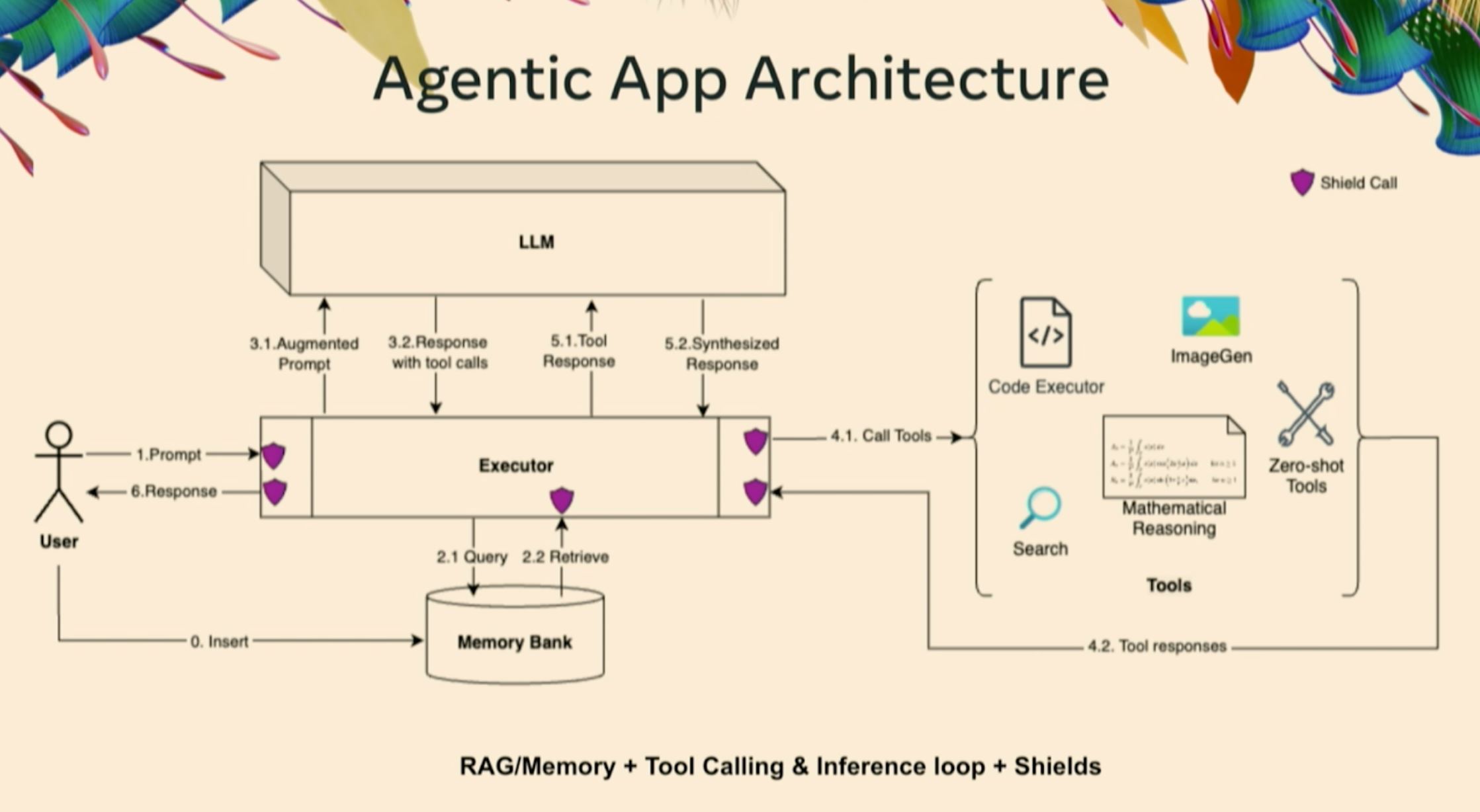

The folks of Meta showed how to build agents with their Llama Stack, providing also a great notebook with many relevant examples, which includes RAG evaluation with LLM as a judge.

A key highlight was their proposed agentic architecture, which features a central executor coordinating all operations, as illustrated below. Just follow the numbers in order to better understand it.

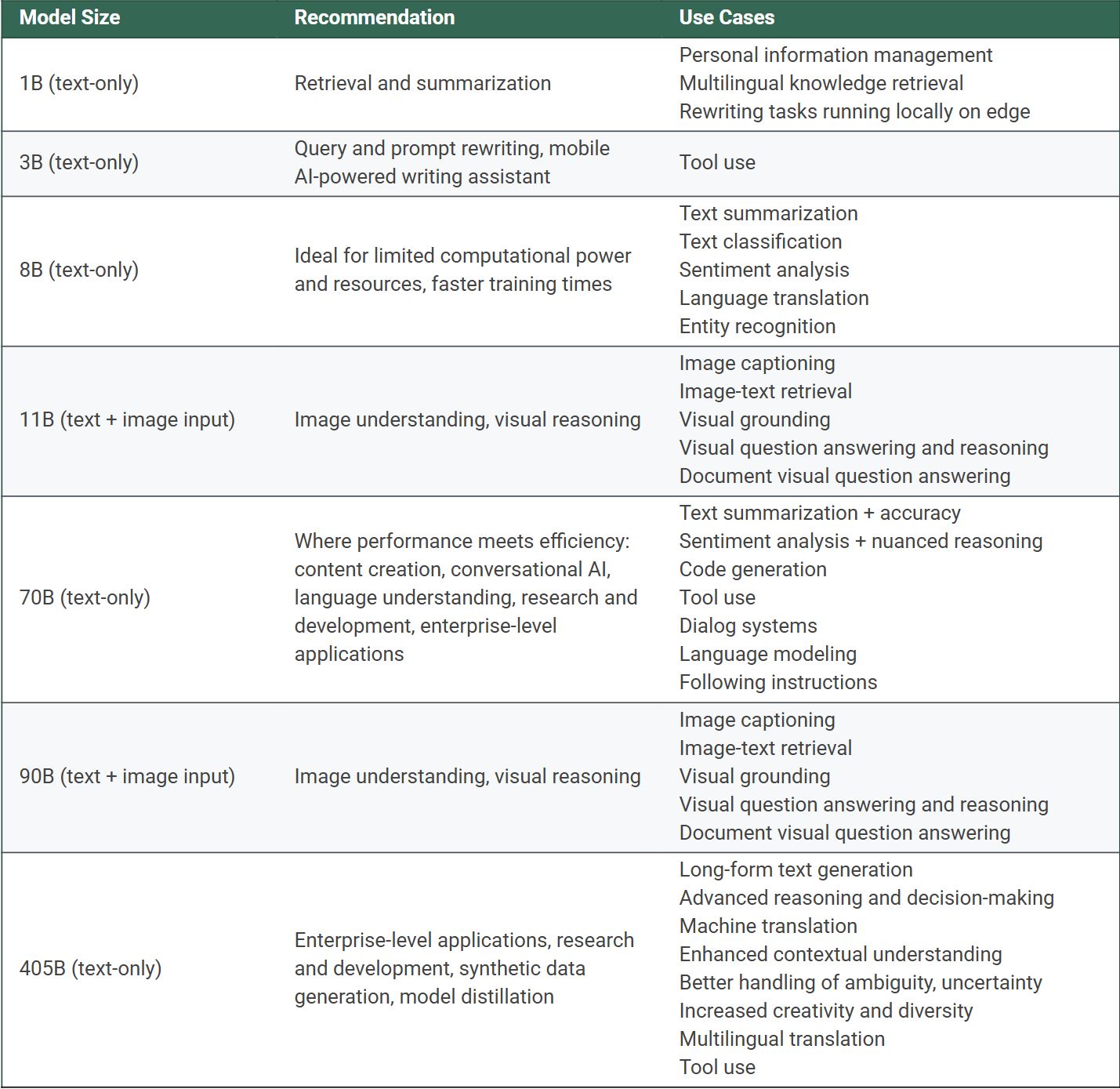

They also provided some hints on which model size to use for different tasks. The following table is quite useful.

Building and improving Large Language Models

One of the standout topics at NeurIPS this year was the process of building and improving Large Language Models. A particularly noteworthy presentation was given by the AllenAI team, who provided a detailed overview of the end-to-end process of building an LLM. From data acquisition to post-training, they shared many insights and tips. This topic is so rich that it deserves a summary of its own, which you can find here.

Are we running out of data?

A recurring theme was data scarcity. Kyle Lo from AllenAI clarified that while data itself isn’t vanishing, open-access data is becoming increasingly limited. Ilya Sutskever, in his remarks upon receiving the “Test of Time Award” for his paper, described data as the “fossil fuel of AI,” noting that while compute continues to grow, data is not growing at the same pace. He suggested that we should be looking at “synthetic data,” inference time compute, and agents as potential solutions.

This was challenged by Jason Weston, who pointed out that significant portion of the training of LLMs in frontier companies relies on “closed data,” which they possess and are generating in substantial quantities. He expressed skepticism about the severity of the data scarcity issue, suggesting that Ilya’s perspective might be influenced by his recent departure from OpenAI and the resulting loss of access to that data.

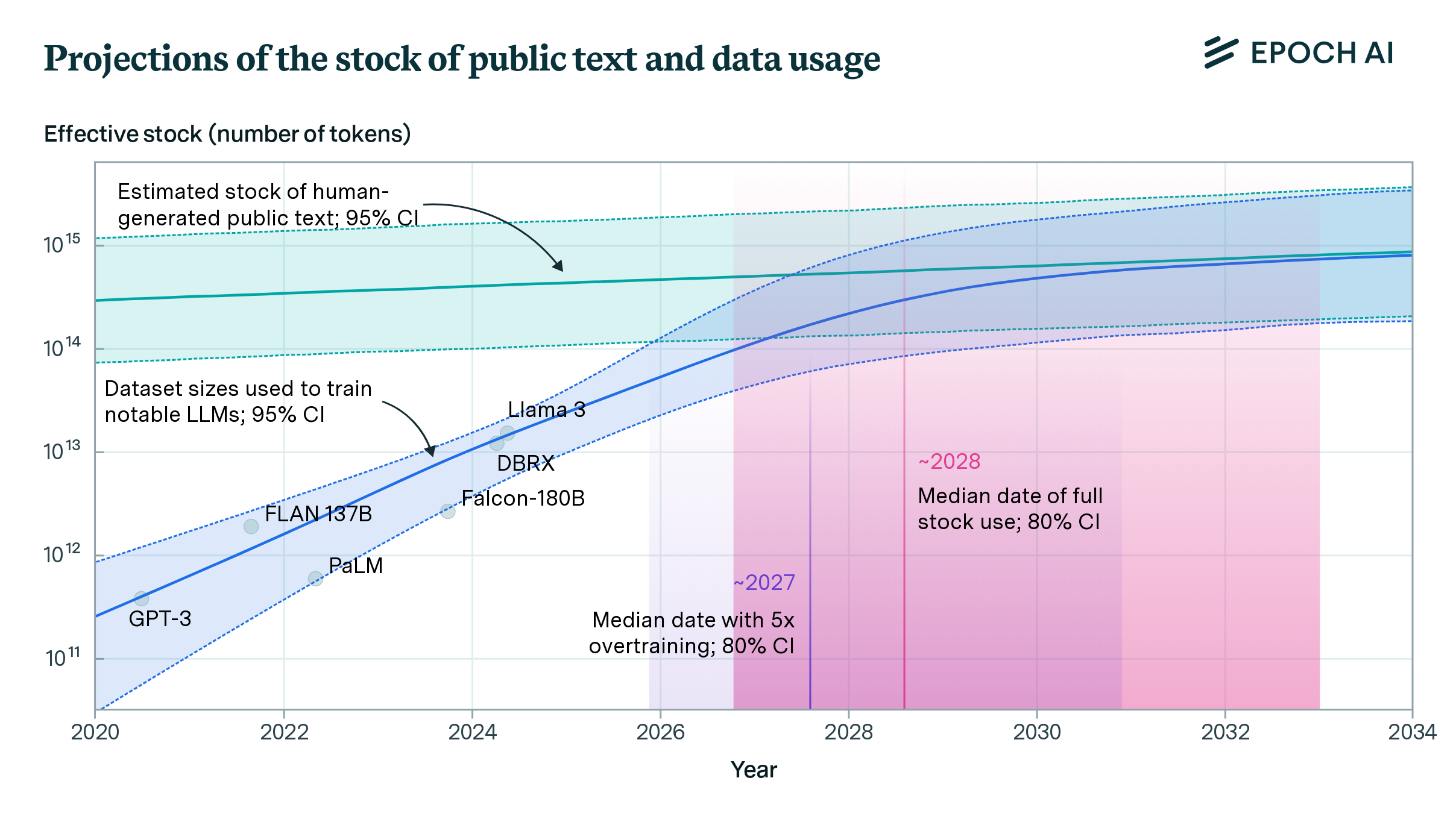

It is worth mentioning the work of Epoch AI. In their Will We Run Out of Data? paper they project that human public text, estimated in 300 trillion tokens, will be fully utilized between 2026 and 2032, or earlier (see chart below).

Epoch AI focuses in this study on textual data. However, a significant portion of data exists in other formats, such as images, audio, and video, which can also be used for training.

While computational power grows exponentially and data increases at a linear rate, algorithms and methods continue to become more efficient. Furthermore, alternatives like self-distillation (model generates data and trains with it), Constitutional AI, synthetic data, and private datasets reduce this reliance on high data volume. For all these reasons I don’t think data will be the main bottleneck.

Architectures and RL methods

It’s clear that other alternatives to the Transformer architecture are standing out, such as Mamba or xLSTM. These architectures are more efficient that the Transformer at inference, as the computing doesn’t grow quadratically with the number of input tokens, while they can parallelize the prediction of the next token in the training, like the Transformer does, instead of sequentially like previous architectures (RNN, LSTM…). Sepp Hochreiter, the creator of LSTM, presented xLSTM, acknowledging its strong resemblance to Mamba.

However, although these arechitectures were mentioned many times, in practice they are not yet widely used.

Additionally, Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (or RLHF), which is the method used by OpenAI ChatGPT to make a language model a chatbot, is being substituted or supplemented by many other methods, like DPO, which is significantly easier and performs at a similar level. More details in my summary on Opening the LLM pipeline.

Measuring the performance of foundation models

Although benchmarking models is part of building models, this topic is so important that requires its own section. Benchmarking is not only important to understand how well a model performs but building relevant benchmarks is key to advance the field.

Benchmarks to advance AI

The definition of intelligence is ellusive, that is why those benchmarks that are easy for humans but hard for AI models are critical, as they establish a new baseline to beat. One of them is ARC, which requires the ML model to solve a series of puzzles, each one with a different logic, like the one shown below.

The performance of humans in the ARC test is very high, around 90% accuracy according to the ARC team, while at the time of Neurips 2024 the best model was at 53%. Interestingly, less than a week after François Chollet presentation in NeurIPS, OpenAI announced that their new o3 model is able to reach to 76% in ARC. A great example of how quickly the field moves!

Melanie Mitchell, from the Santa Fe Institute, also showed during a workshop about System-2 reasoning how current state of the art LLMs fail when some benchmarks are modified in trivial ways. She mentioned an example of the paper Reasoning or Reciting? where in a Python code benchmark, where GPT4 can perform very well, just by introducing a simple change in the way the language works (“now lists index start with one and not zero) the model performance drops drastically. See the chart below.

Building “easy for humans, hard for AI” kind of benchmarks are key to the development of more intelligent models. Indeed, as Fei Fei pointed out in her inspiring presentation (highly recommended!), the ImageNet benchmark that she created was a key element for the rebirth of neural networks in 2012, and the newly coined term “Deep Learning”.

EUREKA: A comprehensive framework to evaluate LLMs

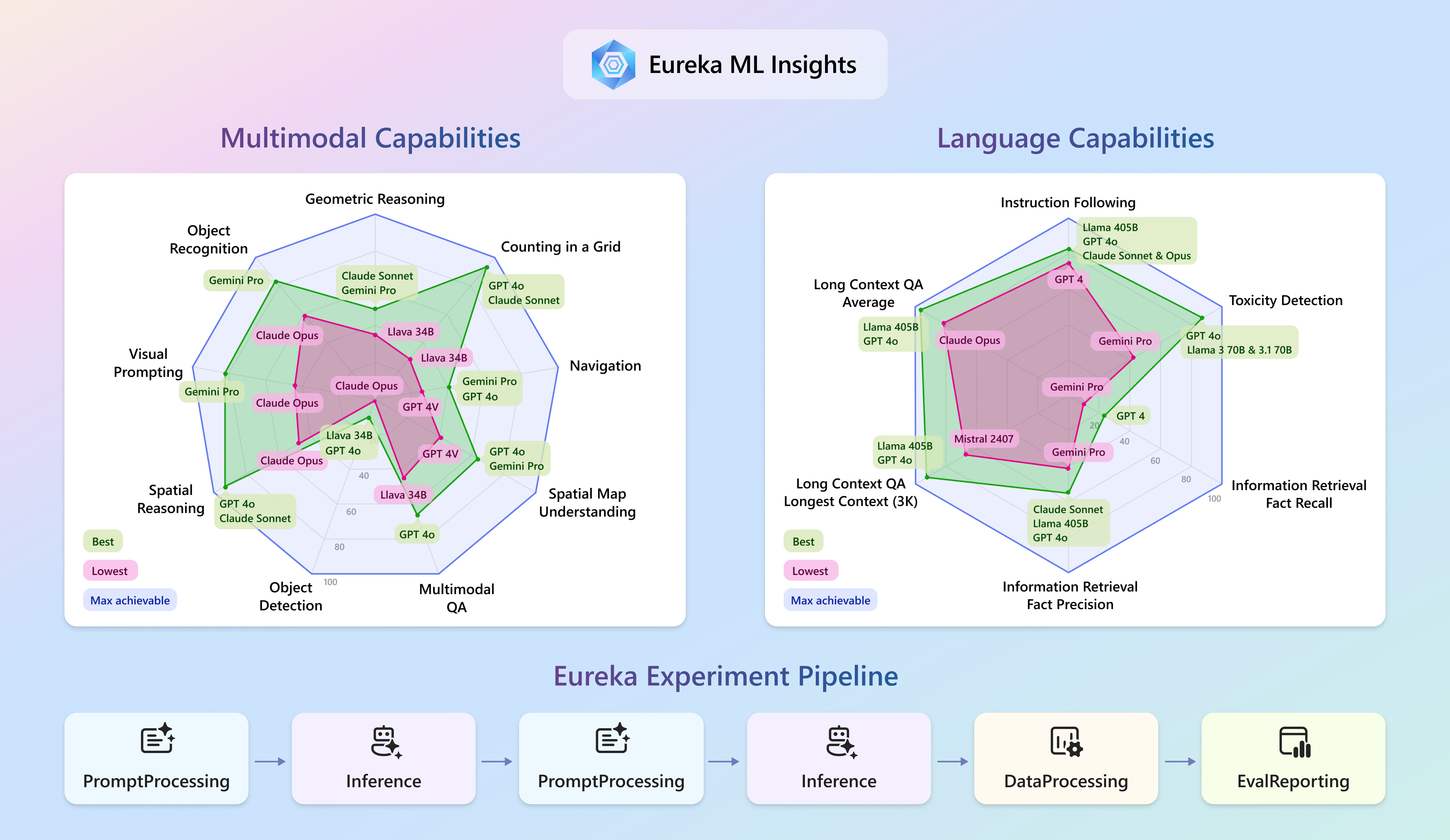

The folks from Microsoft presented a comprehensive and open source framework to evaluate multimodal and language models called Eureka, which assesses the performance of models across several dimensions. Some of the main conclussions of their evaluation of 14 large foundation models are:

- Models like Claude 3.5 Sonnet, GPT-4o 2024-05-13, and Llama 3.1 405B show distinct strengths in specific tasks but are not universally superior across all benchmarks. This highlights the need for task-specific analysis rather than assuming a model’s overall superiority.

- Current AI models struggle significantly with multimodal tasks, particularly those requiring detailed image understanding and spatial reasoning. For example, all models perform poorly on Object Detection.

In the folllowing chart you check see the results for both language and multimodal tasks.

Unified Representations, shedding light on the black box

Significant progress have been done on the topic of understanding how neural networks (human and artificial) encodes and process information. Several illuminating ideas around the topic were presented in the UniReps Workshop at NeurIPS 2024.

The platonic representation

We have substantial evidence that different neural networks, including artificial and human neural networks, converge towards the same way of representing the world. This evidence comes by looking at the multidimensional spaces that the activations of the layers of neural networks produce (an embedding) when a concept is used as input. In The Platonic Representation Hypothesis paper, authors observed that the spaces generated by embeddings of different models have very similar characteristics: for example the distances between points of the same concepts (e.g. distance between the concepts pear and giraffe) in a language model or in a vision model remain very similar, and this similarity increases the better the models are. See chart below.

Not only that, but there is evidence that the same happens with the activation of our neurons in our brain. They also generate a space that is similar to the ones of the frontier models, and we can even use LLM to interpret the output of this human brain activations.

A profound question arises: is there a unique platonic representation that models and humans converge to? Knowing it could help building more intelligent models. If you find this material interesting, I recommend reading the summary of the paper.

Having internal representations encoded as perpendicular vectors also leads to conclude that a neural computation is a transformation of a representation into another representation. That’s the job of the neural network weight and biases, to transform the input representation (usually in the form of learned embeddings) into another representation that is useful for the task at hand. Incredible the power of linear algebra and some non-linearities!

Reverse engineerig intelligence

Many other talks in this workshop where about gaining a further understanding of the mechanics of the brain and neural networks. For example, they discovered that middle layers of LLMs are better to predict the concepts behind human brain activations. There is evidence that LLMs, in order to predict the next token, generate first an internal representation that encodes many functions of the language (which is in the middle layers), which is richer, versus the represenation that just predict the next token, in the final layers.

There is also strong evidence that neural networks encode information in “directions” in a multidimensional space, where each useful abstract concept (for example, the language a text is written in) is encoded in a different direction, each one “almost” perpendicular to each other, which is possible in a multidimensional space (in a 3d space, there are only 3 dimenspossible perpendicular vectors, but in higher dimensions space, if we relax the constraint of perpendicularity from 90 degrees angle to 89-91 degrees, the amount of almost perpendicular vectors grow exponentially with the number of dimensions). Highly recommended to watch this lesson of ThreeBlueOneBrown on How might LLM store facts. In fact, watch all the Deep Learning videos of this channel, they are the best I’ve seen explaining the concepts of the transformer.

Very interesting also the Mechanistic Interpretability talk of Neel Nanda, from DeepMind. Mechanistic Interpretability aspires to reverse engineer neural networks, working on the hypothesis that models learn human comprehensible structures that can be understood. He showed an example where they are able to identify a “direction in space” that encodes refusal, i.e. when the model refuses to speak about certain topic, usually because of the safety constraints. Knowing this direction, they are able to deactivate it, just by subtracting that vector, allowing the model to respond on originally unintended ways. This refusal direction appears in every model they checked, is almost universal.

One clear application of better understanding the inner workings of neural networks is to improve their safety. Which lead us to the next topic.

AI Safety: advocating for tools, not agents

Youshua Bengio and Max Tegmark participated in a relevant workshop on AI safety. One of their main arguments was that AI’s benefits can be maximized while minimizing risks by developing specialized models rather than fully autonomous agents. A great example of this is the AlphaFold model, which is a tool that helps scientists to predict the 3D structure of proteins; key for drug discovery and currently widely used.

Foundation models for E-commerce

The folks from Shopify presented an initiative to build a foundation model for e-commerce, which takes a selection of events as inputs (these are the tokens), and try to predict following events. The idea is that such a model takes many functions of a typical e-commerce platform, like recommendedr system, fraud detection, next best intervention, etc.

They presented a couple of architecture choices to address the problem, HSTU, and TIGER. What is promising about their work is that they mention an uplift of 240-480% recall@10 in offline experiments. I am looking forward to see the results once models are deployed in production.

Concluding remarks

The scale of NeurIPS 2024 is a testament to the rapid growth of the field of AI. The conference showcased a wide range of ideas and approaches, from the development of large language models to the exploration of new architectures and reinforcement learning methods. The presentations on agents and the development of tools for AI safety were particularly thought-provoking, highlighting the potential for AI to transform our world in the coming years.

As a final thought, consider that human intelligence, the most advanced we know (so far), processes 50-100 terabytes of sensory data annually, all powered by a brain consuming just ~20 Watts. This sets an ambitious benchmark for AI systems to aspire to.